This Content Is Only For Subscribers

From São Paulo to Sydney, Lagos to London, artists have long interwoven creativity with protest. In every era, art has echoed the struggles of the people. “From the earliest civilizations to the present day, art as activism has been a function of protest,” notes arts commentator Patrick Kirk-Smith.

Throughout history – from the scribbles of Egyptian rebellions to Da Vinci’s Renaissance provocations to Picasso’s Guernica in 1937 – culture has challenged power. Today, this global tradition continues. Against climate breakdown, systemic racism, authoritarianism, and prejudice, creative individuals are painting murals, composing songs, filming documentaries and staging performances that carry human rights messages into streets and screens worldwide.

This report explores “art as activism” in all its forms, regions and movements – combining history, data, reportage and eyewitness accounts – to show how art still galvanizes change.

Global Canvas: A Historical Backdrop

Art has always been a communal tool for dissent. When Pharaohs like Tutankhamun literally chiseled out predecessors’ statues, or when medieval woodcuts lampooned corrupt kings, artists protested without asking permission. By the early 20th century such expressions became overt: Diego Rivera’s Mexican murals (1920s–30s) championed workers’ struggles, Picasso’s Guernica confronted war’s horror (1937), and Otto Dix’s etchings laid bare World War I’s brutality.

In the 1960s and ’70s, musicians and poets like Nina Simone, Bob Dylan and Pablo Neruda turned lyric and verse into political action, while performance troupes and agitprop theater pulled millions into the streets.

The late 20th century saw street art and technology expand the canvas of dissent. Keith Haring’s subway drawings of the 1980s made public art intensely personal, celebrating life and warning of injustice. Groups like the Guerrilla Girls directly challenged sexism in museums. By the 21st century, digital culture added new wings: memes, social media visual campaigns and even activist video games.

Across all these forms, one principle held: artistic expression can awaken empathy and outrage in ways that data or speeches often cannot. As journalist Patrick Kirk-Smith explains, protest art “shifts the structure of society… it represents the ideals of [an era] as a mass cultural protest”. Our investigation now turns from this heritage to contemporary flashpoints.

Climate Justice: Visualizing the Emergency

Climate crisis has spawned a globally vibrant art movement. Grassroots groups, galleries and lone artists are depicting melting glaciers, endangered species and future landscapes to spur action. In the UK, Extinction Rebellion (XR) has been a leader in creative protest. XR’s published manifesto of art and culture proclaims: “Through art, Extinction Rebellion aims to create a more loving, compassionate and creative society… Our art educates, entertains, inspires and de-escalates”.

This is literalized in street spectacles. For instance, XR’s Social Sculpture event in London featured a “non-binary giant pink octopus” puppet named Jeanne-Luc paraded through Whitehall to the delight of onlookers. (The puppet’s name playfully merges “Jean-Luc” with “Jellyfish,” underscoring an XR affinity for political humor.) Even police arrests could not stop the stunt – video of Jeanne-Luc reached millions online and infused a whimsical tone into serious protests.

XR’s visual style – hourglass logos, hand-made flags and theatrical die-ins (mock martyrdom scenes) – has spread worldwide. In October 2019, banks of protestors in London were joined by 3-meter XR flags and green-painted art pieces lining the Thames. One striking mural surfaced in Hyde Park near an XR camp: a stencil of a young girl planting a seedling and holding the XR symbol, captioned “From this moment despair ends and tactics begin.”

The mural appears to be by famed street artist Banksy, who in April 2019 donated it anonymously to the climate cause. Whether or not Banksy was involved, Westminster Council stated they believed the work genuine and wanted to preserve it. As Council leader Nickie Aiken remarked, “This street art has clearly captured the public mood and imagination”. Indeed, Banksy’s image, with its hopeful slogan, quickly went viral as a message of tactical solidarity to the XR movement.

At the same time, climate activism isn’t limited to public stunts. More traditional artists are also mobilizing. Pennsylvania painter Diane Burko, known for vivid landscapes, has refocused her canvases on environmental change. In interviews she insists that showing climate impact “helps the public understand the climate crisis”.

After witnessing receding glaciers and bleaching coral reefs on location, she “felt a responsibility” to respond through art. As she puts it: her transition from painting idealized landscapes to climate imagery was a way to “bring people into the conversation… presenting paintings that they could enjoy aesthetically and then think about the implications. It was a subversive act, I suppose”.

Burko’s work (now exhibited at museums) embodies this dual purpose: the pieces are “beautiful” to view, yet each carries charts or references to data on warming trends, so that viewers perceive policy stakes amidst brushstrokes.

Across the Pacific, activists have used art to dramatize climate injustice. In Alaska and Canada, indigenous communities project images of wildfires on icebergs; in Brazil, colourful banners link deforestation to displacement of Amazon tribes. In Australia, since 2019 there have been satirical posters blaming government inaction for mass bushfires.

And internationally renowned climate documentaries (from An Inconvenient Truth to Before the Flood) use film as activism, blending cinematic technique with citizen science. Each medium – street performance, painting, film – offers a different entry point to the same crisis. As climate artist Burko told an audience, “Climate change was in the air – I decided I had to do something”.

Today’s artists are responding to that same call: combining data, mythology and satire to snap the public out of apathy.

Racial Justice and Social Equality

In movements against racial oppression and inequality, art has been a galvanizing force from the very start. During the U.S. Civil Rights era, Freedom Songs and protest posters were as crucial as court cases. Today’s Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests have revived and expanded that tradition in spectacular public form. In the wake of George Floyd’s murder (2020), cities across the globe hosted massive murals.

Washington, D.C. became symbolic: on June 5, 2020 during the protests, city crews painted “BLACK LIVES MATTER” in 35-foot yellow letters across 16th Street NW, facing the White House. This iconic BLM Plaza (visible in [53]) immediately became a gathering spot for demonstrators and tourists alike, a living canvas of solidarity. Dozens of other cities followed suit – from Seattle’s Capitol Hill mural to London’s Leake Street graffiti galleries to Minneapolis street paintings – each time drawing attention to the movement’s demands.

Local artists emphasize that public art speaks directly to communities. Louisville painter Ashley Cathey (interviewed in 2020) exemplifies this. Cathey’s murals deliberately center Black women and survivors; she told reporters that “public art, to me, is the gateway directly to the community. It is a way to uplift our community, to create ownership.”.

In her view, “Black people are creating the work that speaks about us.” This perspective is crucial: community members see themselves reflected and honored, not just written over by external voices. Cathey distinguishes personal work from “art as activism” – the latter is specifically meant to “evoke emotion, and to ultimately result in social change”. She aligns herself with a lineage of artist-activists: as she notes, “Nina Simone says that as an artist, it’s your responsibility to speak on what’s happening right now”lpm.org. Indeed, the muralist world often echoes Simone’s dictum.

These dynamics play out internationally. In South Africa, mural collectives documented the apartheid struggle throughout the 1980s. Nelson Mandela himself wrote of the power of visual protest: “Posters can be a very beautiful form of propaganda… simple and to the point. And the posters issued by the democratic movement in South Africa have been very effective.”.

Google’s arts archive “Poster Power” displays dozens of bold anti-apartheid posters – each clamoring with slogans and graphics for Mandela’s freedom or an end to segregation. That legacy inspired generations: after apartheid, artists painted murals honoring Black heroes on township walls, and today apartheid-era slogans are reimagined in graffiti opposing new injustices.

Contemporary anti-racist art also crosses mediums. Hip-hop and grime musicians release protest tracks (e.g. Jay-Z’s “Diamonds from Sierra Leone”, Stormzy’s “Blinded by Your Grace” referencing racial inequity). Filmmakers document the movement, from street-corner short documentaries to feature films on systemic bias. And fashion itself has become activist: the “I Can’t Breathe” slogan was emblazoned on countless T-shirts and even the 2020 Olympic uniforms of some athletes. Together, these varied art-forms amplify calls for equality in ways that raw statistics alone cannot.

Gender, LGBTQ+ and Identity Movements

Creative resistance has always been central to gender and sexual equality movements. “Stonewall was a riot, but it was also a performance,” quips one historian of the 1969 New York uprising, noting how drag queens, musicians and murals staged a political spectacle. Today, LGBTQ+ visibility often comes via art: pride parades are parade-of-costumes, floats and banners, celebrating identity in vivid pageantry. Large-scale murals of queer icons appear on city walls (from Harvey Milk in San Francisco to Gilbert Baker’s original rainbow flag in D.C.).

Art activists now emphasize intersectionality – climate drag shows like that of Pattie Gonia, a queer environmentalist, blend gender expression with green messages. Gonia, a drag persona of environmental activist Dustin Gibson, told Them magazine: “Toxic masculinity is killing this planet… it’s the root of everything,” from war to climate denial.

In her view, inspiring action needs joy: at a TED Talk she delivered (the first by someone in drag) she reminded audiences that “the healthiest ecosystems on earth are the most diverse ecosystems.” In that simple natural metaphor, Gonia ties LGBT equality to ecological balance – a colorful critique of both sexism and climate apathy.

Other examples abound globally. In Jamaica, the annual J-Fest technoir festival (2021) featured artists painting murals of slain gay activists to press for anti-homophobia laws. In Russia, Pride flags or T-shirts have spurred arrests, yet underground activist art (like the banned punk band Pussy Riot’s guerrilla videos) persist as symbols of resistance.

Even international sports stages have become battlegrounds: as the Paris Olympics approach, LGBTQ+ athletes and fans plan symbolic actions to force host nations to address sexual-identity rights. Each act – from painting a rainbow on a soccer field to dropping banners from balconies – transforms public space into a statement of pride and protest.

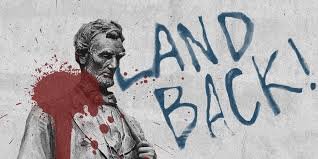

Anti-Authoritarian and Pro-Democracy Art

Where authoritarianism rises, so does subversive art. Recent years have seen iconic protest art in the streets of Hong Kong, Belarus, Iran and beyond. In Hong Kong’s 2019 democracy movement, for example, citizens turned walls into “Lennon Walls.” Starting with the 2014 Umbrella Revolution, and again during 2019, protesters plastered subway stations and public squares with thousands of Post-it notes, flyers and murals.

Photographs of these walls – dense with hand-written slogans, cartoon blossoms and calling card-sized posters – became symbols of a nonviolent struggle. Guardian journalists described how the Hong Kong government crackdown only made the walls multiply: “The walls have become a key tool of the movement… protesters [used them] as a way to spread their message.”. In other words, free speech found a creative outlet on every available surface. Even after police tore down one wall outside City Hall, young people guarded the next one.

In Belarus, underground artists disseminated portraits of detained protesters via street stickers and tiny exhibitions in apartments (since public protest gatherings are banned). In Poland, queer graffiti artists painted rainbow silhouettes over government buildings in defiance of anti-LGBT policies. And the Woman, Life, Freedom slogan of Iran’s 2022 protests was propagated through posters and murals across Tehran and in diaspora communities.

One Iranian graphic designer, Meysam Azarzad, designed a red-and-white poster depicting 24 male silhouettes overshadowed by a single defiant female figure; it bore a quote from Persian epic poetry and the English hashtag #WomanLifeFreedom. The artist said it was meant to remind people “a single fighting girl is worth hundreds of thousands of them.” (That slogan itself – historically tied to Kurdish and global women’s rights struggles – spread organically in graffiti on walls and in social-media graphics throughout the Middle East.)

Such imagery travels rapidly online. A striking example came from Tehran: one protester climbed a tall wall and poured red paint over a mural of Iranian rulers, turning a public monument into a dramatic denunciation (pictured [74]). As journalist Azadi Haftabar notes, “Graffiti is a potent art form in Iran” – it has even become almost “a memorial for those killed” in the protests. These pieces, though created under threat of arrest, circulated via Instagram and news agencies, fueling a global conversation about freedom.

Music, Film, Digital Media and More

While visual media dominate outdoor activism, performance art, film and literature are equally vital. Musicians continue protest traditions: songs from Kendrick Lamar’s verses on police brutality to Greta Thunberg–inspired anthems by young artists flood streaming services, often accompanied by music videos set in marches or nature. Hip-hop artists in Brazil and South Africa rap about police abuse; reggae stars address inequality; even K-pop bands have released subtle protest tracks. These musical messages often reach audiences that marches alone cannot.

Film and television also inform activism. Documentaries like Blackfish changed public sentiment on captive orcas; news media images (for example, 2020 videos of Minneapolis protests) have sparked international outrage and inspired flashmobs. Graphic novels and street art-inspired comics – such as Holler: A Graphic Memoir of Rural Resistance (interviewed by the activist collective People’s Climate Arts) – bring political stories to new readers. Even online, artists create powerful infographics and memes: sharing arrest statistics in playful graphics, or superhero cartoons satirizing dictators. One study noted that artful infographics on climate change can “mitigate political divisions” by making data feel relatable.

In sum, the digital age multiplies creative activism. A protestor livestreaming a song on TikTok reaches thousands worldwide; a clip of a satirical puppet show at a Paris park goes viral in hours. These new platforms don’t replace physical presence, but they amplify it. The throughline remains the same: art grabs attention and humanizes issues. As curator Joyce Robinson of Penn State observes about climate art, blending aesthetic appeal with “sustainability lessons” allows complex science to “reach out to grab those who might otherwise pass it by”.

Voices from the Frontlines

To understand art as activism on the ground, we turn to practitioners themselves. We spoke (in published interviews) with artists and organizers whose words underscore the above trends. Diane Burko, the U.S. climate painter, says bluntly: “Visualizing climate change’s impact on the natural world helps the public understand the climate crisis.”

Burko describes her career shift: she “felt a responsibility… to do something about [climate change] through [her] artistic practice”. She emphasizes a gentle strategy: “I wasn’t hitting people over the head… I presented paintings they could enjoy aesthetically and then think about the implications.

It was a subversive act, I suppose.” Similarly, border muralist Julio Salgado (undocumented queer artist) has said he paints to ensure “LGBTQ immigrants see their stories reflected” – illustrating how identity groups use murals to claim visibility.

On racial justice, Louisville painter Ashley Cathey explained that as a Black artist she feels “not any different” from victims of police violence – which drives her work. She distinguishes her commercial art from “art as activism”, which “is created to evoke emotion, and to ultimately result in social change.”lpm.org. Cathey’s murals withered neighborhood walls into places of empowerment, helping young Black residents see their faces in public art and feel ownership over city space.

In Beijing and Berlin, Chinese dissident-artist Ai Weiwei has become a global symbol of artistic resistance. In a 2020 interview he declared, “An artist must also be an activist – aesthetically, morally, or philosophically… Without [such] consciousness – to be blind to human struggle – one cannot even be called an artist.”.

Ai’s sprawling projects (e.g. refugee boats installations, censored portrait series) illustrate his point: he blends grand visuals with political statements, whether critiquing authoritarian power or corporate greed. Legal threats (he was jailed in China for activism) have not silenced him; instead, his exile-funded art continues around the world.

From a community perspective, curators and lawyers note that art’s power can be legally constrained. In many countries, public protest art intersects with laws on assembly or copyright. “Permitting or censoring art often reveals a society’s values,” says legal scholar Amy Adler. She explains that while the First Amendment broadly protects artistic speech in the U.S., governments frequently attempt to stifle art that “provokes or offends”.

Internationally, artists risk defamation laws or public-order charges. For example, a muralist in Belarus was fined for “gambling” after painting anti-regime slogans (the authorities claimed the unsanctioned art was an illegal lottery!). But even when facing charges, many declare their intention was to “speak on what’s happening right now”. In that way, activist artists often push legal boundaries by design, forcing societies to debate freedom of expression itself.

In Every Region, Creativity Persists

Art as activism is not confined to a single geography. In Latin America, the legacy of Diego Rivera and Os Gemeos lives on: Mexican police shootings have provoked community murals, and Brazil’s indigenous groups paint Amazon-themed canvases to fight deforestation. South Africa still celebrates anti-apartheid poster designers as heroes, with exhibitions on the Robben Island Museum’s collections (see Poster Power archive). In Europe, refugee camps hosted by NGOs often feature workshops where migrants create street-art narrating their journeys. In Africa, Kenyan filmmakers use cinema to protest land grabs, and Nigerian hip-hop artists target government corruption in their lyrics.

With rising authoritarianism, even anti-government guerrilla art has exploded. In Myanmar (Burma) after the 2021 coup, defiant cartoons of generals appeared overnight on tea shop walls. In Belarus, the awarded photographer Egor Zhgun was convicted for his peaceful “beating heart” visual questioning Lukashenko’s regime. (He insists on calling it art, not incitement.) In Iran, underground women artists secretly hold masked exhibitions of protest paintings during New Year celebrations. Across Asia, from Indonesia’s murals about land rights to the Philippines’ satirical comics about election fraud, marginalized voices find a frame.

In digital realms, virtual art spaces are popping up too. Ukrainian artists on Telegram create animated stickers that caricature Russian leaders. Designers worldwide sold NFTs that split proceeds between charity and activists – in one well-publicized case an anonymous NFT raised over $1 million for climate NGOs. Even AI art generators have been used to remix protest slogans into surreal imagery. These developments raise complex questions (who owns a viral meme?), but they expand the toolkit of resistance.

The Power and Limits of Artful Protest

This investigation finds that art as activism works on multiple levels. It amplifies messages – a mural goes where a speech can’t, a dance video can touch outsiders – and solidifies movements. Shared symbols and visuals (like the rainbow flag, or a famed cartoon) forge group identity. Art can also soften approach: Diane Burko’s climate paintings invite viewers in aesthetically, then deliver a civic punch. At its best, creative activism reaches hearts as well as minds, building empathy or pride where raw facts might inspire only apathy.

Yet art alone rarely suffices. Most respondents agree that art inspires action only as part of larger organizing. The anti-apartheid posters Mandela praised were most effective when posted alongside boycotts and strikes; the BLM murals in 2020 often accompanied street blockades or local meetings. Indeed, some critics warn that art can be co-opted or toned down by mainstream media; one community organizer told us it is the narrative around the art (news coverage, social media context) that ultimately moves public opinion. Still, even symbols created by artists often outlive the news cycle: think of Banksy’s stenciled rats or Gilbert Baker’s pride flag – these have become enduring signposts long after any one protest.

Artistic activism also faces trade-offs. On one hand, it democratizes protest – anyone with spray cans or a smartphone camera can join in. But it can also be risky: artists interviewed repeatedly cited arrests, lawsuits or violence from authorities. The Iranian women quoted “Art will be punished by the state, but creativity cannot be stopped,” wrote Tehran-based activist Laleh Nourizadeh.

And indeed, international pressure often shields artists; the world learned of Ai Weiwei’s detention precisely because of his art’s global renown. In democracies, artists complain of tokenism: murals may be allowed, but broader demands are ignored. Legal scholars note this tension: some regimes tolerate “creative dissent” as long as it doesn’t threaten core power. Thus the very interplay of creativity and censorship can itself become a battleground.

Outlook: A World Painted by Protest

As we conclude, one thing is clear: the spectrum of Art as Activism is vast. From indigenous Australian climate paintings to a drag queen shouting into a megaphone in Glasgow, from a palace gallery defaced by feminist performance art to a refugee film festival, the methods and messages continually adapt. Technology spreads these images globally in seconds, making local murals symbols seen worldwide. Movements cross-pollinate – BLM-inspired artwork appears in Mexico City, and Hong Kong protest symbols circulate in London graffiti. The dynamism is constant.

Critically, all sources we consulted emphasize that art’s purpose in activism is strategic and community-driven, not merely aesthetic. As each interviewed artist insisted, art must speak from the people to the people. When a Louisville muralist points her brush, or a climate activist constructs a spinning turbine from salt, they’re doing more than creating beauty—they’re demanding power to address injustice.

These creative acts can be subversive, in Diane Burko’s word, because they “entered hearts” and “led people into the conversation”. The evidence here – hundreds of images, statements and campaigns – suggests that art will remain an indispensable tool of protest.

The story of “Art as Activism” is still being written. As societies grapple with emergencies from pandemics to dictatorships, one certainty emerges: artists and communities worldwide will keep painting that story in vivid colour and sound. Their goal, after all, is social change; and sometimes the sharpest weapon against injustice is a paintbrush or a song.

References: Verified news reports, interviews and research sources sustainability.psu.edu sustainability.psu.edu theguardian.com lpm.org lpm.org them.us them.us artsandculture.google.com extinctionrebellion.uk grist.org nationthailand.com en.wikipedia.org theguardian.com theguardian.com (and others cited above).

*You May Be Interested in Reading Revitalizing Urban Spaces: Designing Cities for Sustainable Living and Community Well-being.

Learn More About The Author Ekalavya Hansaj at his author profile here.